Significant Impacts On These Species Through Direct Use of Their Meat, Eggs, Skin, and Shells

Out of seven species of sea turtles, six are internationally listed as endangered, a fact credited to either direct or secondary environmental disturbances caused by human behavior. Notwithstanding, although threats to these creatures are currently largely ancillary in terms of by-catch, pollution etc, historically humans have had significant impacts on these species through direct use of their meat, eggs, skin, and shells – something which still takes place today across large geographical areas.

Sea turtles crammed together at a turtle farm in Grand Cayman.

On the island of Grand Cayman, for instance, a green sea turtle farm marketed as a rehabilitation center sells turtle meat, justified as an effort to regulate the industry locally. Even putting ethics regarding farming aside, the center has also been widely criticized for its treatment of the turtles. Considering their migratory and solitary nature, it is hard to rationalize a crowded tank as an effective environment for rehabilitating the green sea turtle, and the practices at this center point more broadly to an international trend exposed and made infamous with orcas and dolphins at Sea World as exploitation posing as conservation.

Turtle meat was first eaten in the Cayman Islands during the 17th century by sailors who observed the species thriving in the local waters, and hunting became a large part of their economy until the 1950’s, when conservationists observed the species declining rapidly and attempted to halt the practice. This pushback, however, increased prices, leading the meat to be seen as a delicacy, which was also thought to hold medicinal value. Today, many of the early meat preparations are still used as the signature dish of the Grand Cayman Turtle Center, such as turtle meat stew which can be found at many of the restaurants in the area.

Turtle Eggs for sale in a market in Malaysia.

Central America is another area one can find sea turtle meat or eggs on or off-menu. Surveys suggest that internationally, 42,000 sea turtles were killed legally in 2014, and Nicaragua accounted for 22.6% of that number, making the country responsible for almost 10,000 deaths annually. With illegal turtle deaths also taken into account it is probable that number is much higher. While poachers assume direct responsibility, consumers are also contributing to this crisis by participating in the unregulated market.

Efforts in Nicaragua have been made to alleviate the consumer demand for turtle meat by generating parallel economies around tourism, with companies typically collaborating with local turtle nurseries. Additionally, visitors being given a chance to observe hatchlings closely tends to generate sympathy for the turtle and their deteriorating numbers.

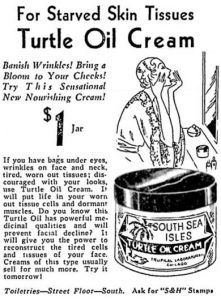

A South Sea Isles 1932 ad for Turtle Oil Cream

Historically oil has also been extracted from turtle eggs for cosmetics. This gained popularity in the western world in the 1930’s where it was advertised in creams to decrease signs of aging. In 1957, Estee Lauder proudly released their “Re-Nutriv Creme” containing turtle oil, and similar examples were seen until the 1970’s when social pressure and new conservation laws pushed cosmetic companies to either discontinue the product or rebrand it to not include the oil. Although not common, sea turtle oil products are still available online. Products that still use turtle oil in their branding typically do not have turtle oil in their ingredients but contain a biomimetic substitute, which is seen in “Kryst Turtle Oil Cream.” While recognizing it is illegal in some countries and discouraged in many, turtle oil holds a prestigious reputation in products.

The cultural and artisanal use of sea turtle shells, typically from the Hawksbill, dates back to Ancient China. Oracle bones, an example of an object frequently made from the bottom of the turtle shell, or plaustron, were used for fortune-telling and held cultural significance during the late Shang Dynasty. Japan also has played a part in the industry, with turtle shells having been imported there as early as the 1700’s for tortoiseshell, or “bekko,” style art. The overlapping gold and brown hues were appealing for accessories, decor, and jewelry. Despite the species being recognized as critically endangered today, the demand for the unique hawksbill shell persists. Sea turtle skin from any species (but more typically from Olive Ridley turtles) is seen used for leather goods, but this practice has a much more recent beginning in the 1970’s.

CLICK HERE TO READ ABOUT EFFORTS TO SAVE THE HAWKSBILL

The beauty of a Hawksbill Sea Turtle’s shell had made it attractive for jewelry and accessories.

Turtle poaching has historically been widespread, but with increasing social awareness and depleting populations restrictions have significantly limited the ability for it to continue in many regions. While this has made turtle consumption and trade more taboo, it also has increased driven it underground and increased its value.

The turtle’s slow movement and diverse use makes them highly susceptible to poaching, and as this persists sea turtle populations will continue to suffer. Informing both tourists and locals alike to the hardships the species face and their marine importance is imperative to their conservation because it decreases the likelihood they will contribute to the industry. Reading labels for turtle oil, choosing reputable eco-tours and not participating in the shell market are all increasingly used practices by consumers. If no-one is interested in consuming, wearing, or displaying sea turtles, those who are continuing to invest in the market may seek business elsewhere and one of the main threats they face can be eliminated.

Isabella Fix is a freelance writer whose work focuses on social and environmental issues.