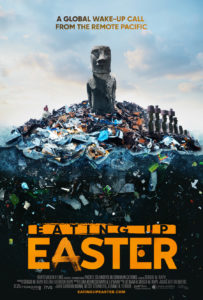

A Native Son Returns Home to Premiere His First Feature-Length Documentary

On March 15, 2019, our team at Plastic Oceans International was proud to present the Easter Island premiere of Eating Up Easter, a new feature-length documentary from director Sergio Mata’u Rapu. It’s a powerful film that examines several social and environmental issues that are front and center on the island, providing lessons for us all, no matter where we call home.

It was honor to have Sergio with us to present the screening, as it is to offer this short Q&A him. You’ll find the official trailer to the film at the end of this interview, but it can also be viewed HERE.

Eating Up Easter director, Sergio Mata’u Rapu.

What’s your background in filmmaking and what first inspired you to want to jump into this often challenging field?

I’ve always loved fairy tales, and the lessons behind them. Growing up in Rapa Nui, we only had one TV channel and the transmission started at 6pm and ended at midnight – so my exposure was a bit limited when I was young. Later, we moved to Hawaii where a very influential high school teacher explained to me how powerful the media was in not only educating and inspiring, but also influencing public opinion. From that point on, I decided to study it and was fortunate enough to get a degree in production from Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles. Once I knew how to use the tools, I loved it even more. The way images on a screen to spur emotion in those watching it was incredibly fascinating, and I realized that this is the space I wanted to work in. As I became more experienced in the field, I wanted to start telling stories of my own people because I often saw others talking about our statues but never talking about us, and for that reason few people even knew there was a living community on Rapa Nui. I finally had the tools to make it happen, but of course it would take a long time until I was able to make my first film about my own people.

You have an interesting background, in that you were born on Rapa Nui, but predominantly grew up elsewhere. What is the Sergio Mata’u Rapu story?

Ha! Well, I do believe that you will find an “interesting background” in anyone’s life story if you dig deep enough. But yes, being from Rapa Nui has cemented many aspects of my life but so has being from a multi-cultural family. My dad is Rapanui, which is where my name, my lineage to the island, and my connection to the culture comes from. My mom is American, who not only taught my sister and I English, but introduced us to the West and eventually got us into American schools in Hawaii – an education which continues to be far superior than what is available on the island today. I met my wife, an American anthropologist and co-producer on the film, on Rapa Nui. In many ways, our love of the island and its people has been the greatest touchstone of our marriage, first in working on this film together, and now becoming parents to our two young boys who we are raising in Minnesota. In short, my life has been about balancing two worlds; Rapanui and the West. The strange thing is that I am neither an insider or an outsider in each. I feel accepted in both worlds. It reminds me that we are all really just one giant community strewn across continents and islands. In that way, I guess, I have followed the family tradition of being an anthropologist with a camera. I love to study people and what they do because I know that everyone’s story is complex but also very similar to my own.

My wife Elena and I set out to make a documentary about the present day issues on Rapa Nui. We, like many others in our generation, were seeing the massive changes happening on the island due to the booming tourism industry and rapid development happening. We wanted to tell a story that would educate travelers to the realities of this “picture postcard” island most of them had on their bucket list. Food security has always been a concern on the island. Though most islanders own parcellas, or agricultural fields, few of them actually plant in mass enough to feed the demand of the entire island. No studies that I am aware of have been done on how much is imported from Chile but I can easily say that at least 70% of what is consumed on the island is brought in by ship or plane. So we set out on an investigation of why this was happening, but as we started to understand the demand of food on the island we realized a larger web of issues around it – trash accumulation, demand by not only tourists but locals, change in culture and behavior, struggle between “need” vs. “want.” These were all issues faced by any developing community, but the difference here was that on such a small island you could see the changes happening quickly, as well as the possible solutions.

Your father is featured in the film as one of the primary subjects. Any specific challenges that came with that?

Well, I won’t lie. As an important leader and politician on the island, my dad has influenced me greatly in my life – but when it came to this film he did not play that role. Throughout the course of filming, we documented his process in building the first shopping center on the island to try and get a better sense of why he thought this was important to have. It is easy for someone not from the island to say “No, the island should stay simple and rustic without all of those buildings and production” – admittedly, I have had those thoughts too. Really, those who say that are people who have those luxuries at hand. Why shouldn’t the Rapanui benefit from the scientific and technological achievements aiding the rest of the world? It is conversations with my dad that helped me reach this other understanding of progress; placing the Rapanui on par with other communities in America or the West ensures that we continue to be active progressive citizens of this planet. In the process of filming, I have come to understand my dad and those other Rapanui from his generation better. Much of their actions were taken because of the scarcity they grew up in, and in doing so it has set the foundation for my generation to take over as leaders in the community.

Mama Piru, who passed last year, is also featured in the film, and certainly had her share of scene stealing moments. In the film I saw a person that had so much depth. Fiery, passionate, funny, kind, intelligent and proud. And as we found on the island, is revered wide and far. What can you tell us about working with her and her as an individual?

Mama Piru was intimidating. You can see it in her first scene of the film. What made her intimidating was that she was honest about how she felt – about you, about your friends, about that camera in her face. The amazing part is that not once did she ask us to turn off the cameras, or to take a break, or to not film some part of her life. She was open and welcoming to our crew throughout the process. I remember when we showed up at her home early one morning to film with her, she prepared tea and breakfast for everyone and reprimanded me for not allowing my DP or camera operator sit down to eat. Food is the big connector on Rapa Nui, as it is in most island communities. Her home was always open to come and have a bite, or rest and talk with her. It was an older way of being, a type of Rapanui that existed back before the plastic bottles, and the paved streets, and the planes. It was this older way of being where so much of her admiration came from. She truly had mana, that ancestral power that was said to be passed down through the generations. We are so thankful that our film will embody a glimpse of who she was, so that my children will know her. But I miss her. We all still do, very much.

The truly powerful and original Mama Piru, in a scene from Eating Up Easter. Photo: Mara Films/Kartemquin Films.

Much of the film deals with cultural identity and the challenges that many indigenous cultures have in maintaining it in this ever-globalized world that we live in. What can you tell us about your own cultural identity and your connection to Rapa Nui. Do you ever see any conflicts in living in two different worlds. Give us the good, the bad and the ugly.

Honestly, I have no conflict in living in two different worlds so long as I remember the good and bad in each. It has become increasingly important for me to be open and not shy about my identity in the West while also not feeling ashamed that I cannot dance or speak the Rapanui language fluently while on my island. For example, on Rapa Nui the connection between people is very important so you are always taught to greet everyone in the room when you enter into a new place. This is not the norm in the Midwest, nor is hugging, but I do both proudly as long as I am not harming anyone. In Rapanui, I used to feel a bit like an outsider because of my lack of skill or talent in the cultural arts until I realized that my skill at speaking English or navigating the American system can actually be beneficial to others – so I try and be as generous as I can with my connections and talents in those areas. So many of us live outside of the island that I no longer feel that my identity needs to be defined by how well I can carve a statue or play the ukulele. My intentions and my actions define who I am no matter where I live.

What was it like to be on Rapa Nui again? Anything you can share as far as what it means to you emotionally, spiritually, or otherwise?

I was a bit scared to go back. Knowing how quickly things change I did not know what to expect. I knew the drug problem was getting worse. I knew car congestion was at an all time high. In addition, several months prior to us arriving there had been multiple violent attacks between Rapanui of the type that the island had never seen before. My community was changing, but I didn’t know how or if it could even be stopped. But once I was on the island, my fears subsided a bit. People who I had not seen in ages greeted me on the street. Family invited me out to eat. People welcomed me “back home.” Everyone knew why I was there, thanks in part to social media, and were proud of my accomplishments. All of this reminded me that for as many problems as my community is going through, they still see themselves as a community.

What message can we all take away from your film, no matter where we call home?

In the film we present the following question: If in order to preserve the island that we love, he had to let go of the things we love, could we make that choice? For us, this is the biggest lesson in the film. Our impact on our planet is largely due to the choices that we have made as a society in what we need to have – cars that emit C02, take-out containers, single use straws. If we remember that these are simply choices, meaning that there are alternatives, then we can take control on our own impact on our planet. And the best part, is that this relates to other aspects of our life as well; health, finances, happiness. But don’t be mistaken, I am no feel-good guru. Elena and I fail a lot in our efforts to be more green, to produce less trash. We all do. The point is to keep trying and moving forward, because we are all in this together.

On a small scale, we are all impacting Rapa Nui. Our shores receive plastic form all around the world – everywhere! So that plastic straw you used last night, that might arrive on my beach in five years. But in the grander scheme of things, we have forgotten that we are all living on a small island. This is a closed loop when it comes to our environment, our politics, our survival. Let’s keep striving for solutions to our greatest problems because we are all in this together.

One of my highlights while on the island was the screening of Eating Up Easter at the Toki music school. It appeared to be a highly emotional moment for you. Take us through what that experience was like for you, including how you think the local community responded to the film.

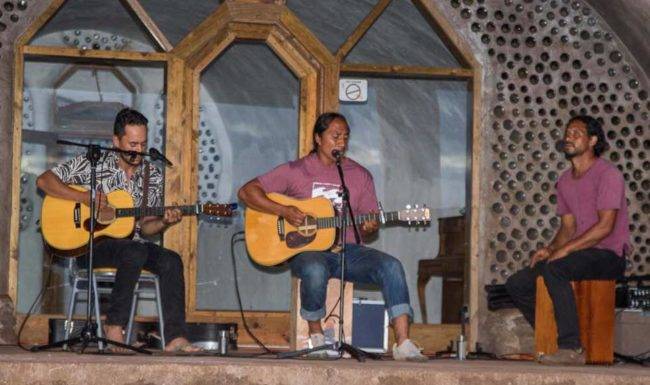

The screening was wonderful. We had an umu tahu the night before – a traditional blessing that is done at the start of an event. On the day of the screening we actually had a few technical issues at the beginning, which I didn’t really stress about because somehow I knew the island was on my side. Then out of nowhere, two different people showed up with laptops that helped us solve the problem. People started to gather earlier than expected, and musical performances lasted longer than I had thought they would, but no one got frustrated or left early. Storm clouds did drift past at one point, but not a single drop of rain fell down on us.

The two points that I feared the most that night were when 1) when I introduced the film in my mangled Spanish thanks to my lack of speaking it in the US and 2) after the credits role when people are free to give me comments. In both instances I only felt love and support from those present. During the intro I received a loud applause when I shared our intention for making the film; to change the external idea that Rapa Nui is not an example of collapse and disaster but instead of solutions and revival. After the screening, many people hugged me in thanks, their voices filled with emotion.

Early on in my career I was taught that it doesn’t really matter if an audience understands your story, but if they walk out of your movie with a smile on their face or tears in their eyes, you have succeeded. That night, I knew we had succeeded.

Speaking of Toki, what an amazing organization, and one operated by some extremely impressive people. What can you tell us about them?

Toki is an amazing group of young men and women, all professionals in a variety of different disciplines, who have a common goal of creating positive change on Rapa Nui. The organization started as just tuition-free music school for the children of the island to learn traditional songs as well as classical instruments (violin, cello, piano, etc.). They have since expanded to start planning a variety of fruits and vegetables to tackle the food security issue on the island, as well as do cultural exchanges with different educational institutions from outside the island so as to build more connections and “bridges” for the Rapanui youth. Even today, there is no community center for the children of Rapanui to explore extra-curricular activates that are guaranteed to be free of alcohol or drugs. Toki is filling that incredibly important need.

In hindsight, is there anything that you would do differently with the film?

Well, yes. I would have wanted to shoot with higher-end cameras so that the quality was consistent throughout. We shot with six different types of cameras over the six years because of budget constraints – so I guess in hindsight I should have tried to either get more money or ask for bigger favors ☺. But no, both Elena and I are really happy with how the film turned out. Finding the story during post production was probably the most painful process, but it needed to be done and we were able to create something that we, as well as the rest of the Rapanui community, are proud of.

What’s next for Sergio Mata’u Rapu?

We have build some great partnerships because of this film and hope to leverage those to find our next story. Elena and I have realized that the stories we are attracted to are those where interesting individuals are set against complex issues. Life is not black and white – many times it’s messy. Like in Eating Up Easter, the real way of understanding an issue is by living with the people who are in the middle of it. That is where we hope to find our next film.

Please Enjoy these Images from Pathy Hucke Atan:

###

Trackback: https://stealthex.io

Trackback: เรียนต่อจีน

Trackback: ufa191

Trackback: click this site