Incorrect Disposal of COVID Protective Gear is Creating A New Obstacle for Our Oceans

The demand for personal protective equipment has never been so high. With the coronavirus pandemic, governments and agencies like the World Health Organization (WHO) are advising the public to equip themselves with face masks and other essential gear to limit the spread of COVID-19. While they have proven effective in the fight against the virus, they also run the risk of being disposed of incorrectly, entering our waters and adding to the already immense and still ever-growing problem of ocean pollution.

A recent post by the French non-profit group Opération Mer Propre (Clean Sea Operation) surfaced on Facebook showing dozens of masks, gloves, and bottles of hand sanitizer submerged throughout the Mediterranean Sea. “How would you like swimming with COVID-19 this summer?” asks Laurent Lombard, the founder of the group. Now, the organization is sounding the alarm over the increased sightings of coronavirus waste, warning that it could become a serious obstacle in the fight to keep our oceans clean.

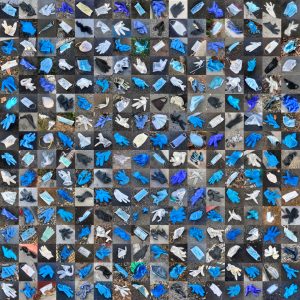

256 discarded masks and gloves, thrown to the ground. Photo: Janis Selby Jones

Beaches in France are not the only places where coronavirus waste has been located. Groups like OceansAsia from Hong Kong have reported an influx of surgical masks on the coasts of the Soko Islands, and Surfrider has recorded a number of single-use masks, latex gloves, and other protective equipment from its multiple beach cleanups around the United States.

The production of personal protective equipment has skyrocketed throughout the pandemic. A recent study published in the Environmental Science and Technology journal estimates that nearly 130 billion facemasks and 65 billion gloves are being used each month around the world. While they are much needed to ensure personal safety, it is important to recognize the danger that these staggering figures pose to our oceans and marine life.

“Plastic pollution is already a huge problem in our oceans– all of our water bodies in fact– and it’s not something that is notional for the future,” says Mike Alcalde, a documentary filmmaker and expert from the México Natural organization. “It is here now, doing huge amounts of damage. It’s ironic that in dealing with the coronavirus crisis we are stacking up difficulties for another one in parallel.”

The increase in coronavirus waste has quickly become a new threat to the world’s oceans, adding to the already growing problem of plastic pollution. According to the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, an estimated 8 million metric tons of plastic enter our oceans every year. If current trends continue, there could be more plastic than fish, by weight, in the ocean by 2050, a recent study warned.

Based on these figures alone, scientists have a good reason to be alarmed. When plastics enter the ocean, they become a long-term issue for the environment due to their inability to biodegrade. Commonly used plastics found in water bottles, drinking straws and fishing lines are virtually indestructible, decomposing only in the presence of sunlight over hundreds of years.

But single-use masks, gloves and other personal protective equipment are no different. These plastic-based items have experts like Gerardo Peña, a marine biologist with Ninth Wave Global, concerned about the catastrophic risks that could arise from the improper disposal of coronavirus-related waste.

“When we talk about medical disposal in the environment during COVID-19, we tend to think about latex and vinyl gloves, which are not different to a plastic bag,” says Peña. “We also have masks which, due the great variety and amount, are almost impossible to assess in terms of direct damage on the environment. The polymeric, plastic-based masks will last decades before nature can find a way to get rid of them.”

When these plastics do start to break down, however, they produce tiny fragments called secondary microplastics, which contain chemicals and pollutants that can also harm wildlife.

“We used to only focus on large animals like whales, dolphins and turtles ingesting large plastics or getting stuck in them, but now we are also looking at fish, shellfish and crustaceans ingesting microplastics created by improperly disposed plastic waste,” says Peña.

Microplastics that are taken up by marine life can accumulate in toxicity and create adverse health effects as they move through the food chain. This occurs through a process known as biomagnification.

“Nobody knows the rate at which biomagnification will increase, but believe me, this is nothing compared to the amount of disposables that we already produce.”

“We are just adding fuel to the fire, a considerable amount of fuel,” adds Peña.

Despite these new challenges, there is hope that, over time, people will begin adopting reusable alternatives such as cotton facial masks to keep each other safe. The importance of proper medical waste disposal is also an issue, but many are optimistic that hospitals and governments will do their part in keeping coronavirus-related waste off the streets and out of our waters.

While public health and safety remains the number one priority of government officials around the world, Peña and others argue that we have to take care of our wildlife just as much as each other.

“The pandemic has already taken a toll on human life, but what makes us think that marine life is different?” he asks. “We already have large amounts of trash in the ocean, and we all need to do our part to avoid making this problem bigger than it already is.”

Zachary Huang-Ogata is a freelance writer specializing in science and the environment. He is a current undergraduate student at the University of Pennsylvania and has worked with various environmental groups and institutions to support their sustainability efforts.