Before Plastics, The Yucatan Peninsula Was Home To Globally Exported Natural Fibers

Stand on the pier in the historic port of Sisal, surrounded by the impossible blue of the ocean, and there is nothing to remind the passing visitor of the vast industry that ruled what was once a major commercial hub. Today, Sisal is a sleepy little town which has forgotten its historic purpose, its citizens harboring a vague memory of their ancestors and the historic wealth of the town, in excess of a century ago.

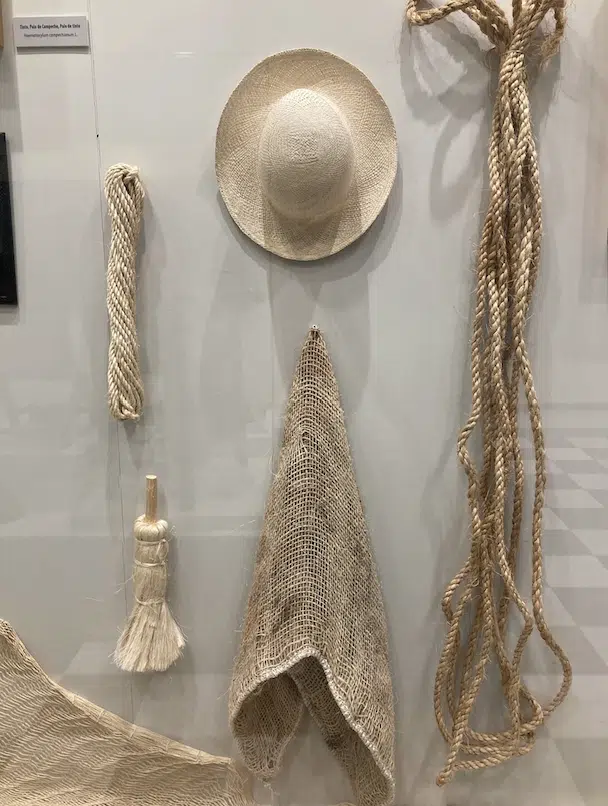

Named after Sisal rope and its source, the plant of the same name, the port was a central point of its distribution, as well as for the related henequén plant, both of which were of major importance in the international textile industry of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The fibrous plant had its threads extracted and then woven into larger ropes, a vast industry based in what were vast haciendas, which today would be best understood as something akin to the plantations of North America – only here the slaves were Mayans, not like those of African descent who had been shipped in further north. Throughout the nineteenth century, in fact, the Yucatan peninsula was the only place on earth where these plants were grown, and later exported, and although the industry stretched internationally to other countries in the early twentieth century, the region remained the largest producer of these textiles until well into the century.

Henequen being loaded on offshore boat at Sisal, Yucatan, Mexico 1924. Photo: Creative Commons

Although there are a wide variety of plants from which these threads were extracted, the plants all generally belonged to the Asparagaceae family, naturally existing in the region and which had been an important source of material for the Maya for centuries, as well as other neighboring communities. Indigenous communities valued these products, and managed them for centuries prior to the arrival of the Spanish, referring to it as their ‘green gold.’ The strength and versatility of the material meant that it was used for decorative and ornamental purposes, but also in construction and transportation. It would hardly be an exaggeration, in fact, to consider these fibers as being the most significant raw material for the pre-colonial Mayan civilization.

The beautiful textiles of henequén. Photo: Meet You In the Morning

Soon after the boom period of 1880 to 1915, however, and an accordant growth in the wealth of the hacendarios, or landowners, the industry began to decline. In part this was fueled by the usual overextension which is a by-product of success – by the early nineteenth century an incredible 60% of the landmass of the state of the Yucatan was given over to henequen plantations, numbering in excess of 1,000 haciendas – but of course much more specifically by the emergence of our great, modern antagonist: plastic.

Because even during the heyday of these natural fibers, synthetic materials were already successfully being developed. In the late 1890’s, British chemist Charles Frederick Cross was successfully developing products which would later come to be known as precursors to modern plastics, and only a few decades later, nylon and polyester were to become ubiquitous, razing the previous landscape by which the world – within short, living memory – which had built itself on natural materials, was fully redrawn and reconstituted.

Henequén drying process in Mexico. Photo: Government of Mexico

In 2021, the global worth of the synthetic fibers market was valued at USD$148 billion, and was projected to grow to USD$160 billion in the next year alone. By 2026, it is expected to reach a staggering USD$226 billion.

But despite the unimaginable scale of the industry as exists, and even more so as it is projected, not all is not lost, because back on the ground in the Yucatan, new fair-trade companies such as Sisal Tejidos are going back in time to get to the future, gathering old processes and values, establishing new markets, and making the argument for sustainable alternatives to plastics.

Just because something is projected doesn’t mean we are unable to affect the outcome. And often stories from the past, or more specifically from our ancestors, can be our guides.

Because the future really is out there; we just have to work a bit to find it.

Jon Bonfiglio is a broadcast and print journalist, as well as Managing Editor for Plastic Oceans International’s written content.

Trackback: university iraq