Big Changes From An Economic Giant

For decades, China has been seen as the global bête noire of climate action. Notwithstanding an intensifying climate crisis, and subsequent geopolitical pressure to reduce its carbon footprint, this vast and complicated autocracy has made little environmental progress.

There are concrete reasons for this: with its sheer size, record population, and dated energy infrastructure, transforming China into a renewable society would be a mammoth task for any government, and would require sustained, incremental change. Thankfully, reports from Shanghai suggest that a solid step has been taken in this direction.

With a new policy that bans single-use plastics in major cities, as well as other recent legislation, hope is emerging that the world’s most populous nation may finally be ebbing towards serious pollution reform.

Plastic pollution and managing plastic waste has long been a problem in China.

In proposals published on November 30, China’s commerce ministry stated that all restaurants, e-commerce platforms, and delivery firms will be forced to report their utilization of single-use plastics to Chinese authorities, as well as submit formal recycling plans. This builds upon the government’s September decision to ban single-use plastic bags and eating utensils in major cities, and single-use straws nationwide, by 2021. For a nation burdened by significant barriers to change, these reforms mark historic progress in addressing what is the greatest source of plastic pollution on Earth.

IF YOU’RE ENJOYING THIS ARTICLE, PLEASE CLICK TO DONATE TO SUPPORT ONGOING CONTENT

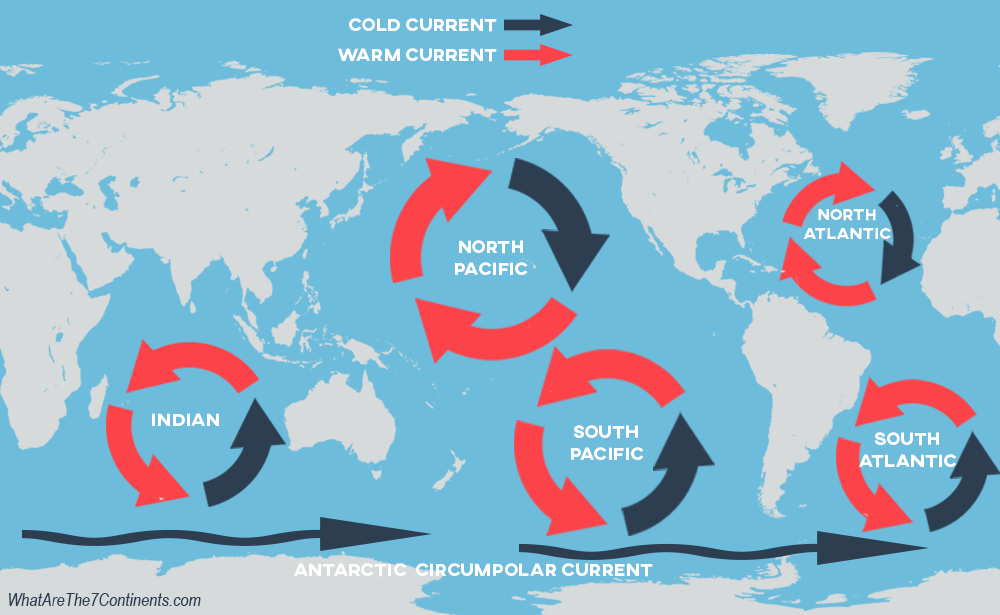

Six of the ten rivers carrying 90 percent of all ocean plastic are found in China. As the infamous Great Pacific Garbage Patch reminds us, this plastic does not simply disappear; most of it remains in the ocean for centuries, traversing the world in massive current systems called gyres. These silent behemoths glide from continent to continent, carrying cities of oceanic debris with them – like the 29,000 rubber ducks lost from a stray shipping container in the North Pacific, which were found on the coast of Scotland, and debris from the 2011 Tsunami in Japan, which washed up on the shores of North America just 10 months later.

The five ocean gyres.

Gyres underscore the unfortunate reality of climate change: more often than not, the effects of pollution do not stay isolated to the area of the source – they compound as part of a global system. In the context of marine ecosystems, this carries grave consequences, for what happens in one body of water can damage life thousands of miles away.

Additionally, given that environmental passivity is often justified in the name of economic growth, it is important to note that plastic pollution is costly. The United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) estimates that marine ecosystems suffer USD$13 billion a year in damages due to plastic waste. Furthermore, the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation estimates that costs to the fishing, tourism and shipping industries of the region surpass USD$1.3 billion.

When all is said and done, however, the primary concern is not monetary – at least it shouldn’t be. As Dr. Charles Rolsky – Director of Science for Plastic Oceans International – explains, plastic pollution has grim implications for the global warming crisis: “When sunlight and polluted plastics interact with one another, there’s a really dangerous exchange that takes place. The UV radiation and heat from the sun causes the emission of greenhouse gases from the plastics, such as ethylene and methane. We know that the planet is warming due to climate change so as this increases, so will these greenhouse gas emissions from polluted plastics, thus contributing to climate change in a vicious cycle”.

Thus, the plastic bags that float down the Yangtze don’t just choke sea turtles – they exacerbate the processes that are bleaching the Great Barrier Reef, melting the Arctic Sea Ice, and cultivating stronger Harveys and Katrinas. This cements the dire need for comprehensive pollution reform – especially among the world’s worst polluters.

“We can’t quit plastic cold turkey,” continues Dr. Rolsky, “but there are steps we can collectively take which move us in the right direction. If we eliminated the usage of most single use plastics, for example, that would be an enormous burden lifted off of waste management, recycling centers, and the environment.”

China’s recent reforms are not revolutionary, but for the nation tasked with a more comprehensive and exhaustive transition than perhaps any other, stricter plastic regulation is cause for optimism. Whether or not these changes mark a new period of Chinese environmental engagement remains to be seen – but for now, we can relish in what is undoubtedly a climate victory.

Isaiah Maynard is a writer from Connecticut. His work focuses on environmental studies and psychology, with a particular focus on how different psychological phenomena influence our perceptions towards and willingness to act on climate issues.